How '10 Cloverfield Lane' earns its title

By Isaac Handelman

For those of you who haven’t seen ’10 Cloverfield Lane’ yet and want to get the optimal viewing experience, I’d suggest not reading anything about the film before you go and see it. Which would mean not reading this piece. You’ve been warned.

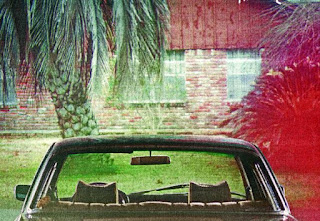

Dan Trachtenberg’s directorial debut 10 Cloverfield Lane will undoubtedly draw up discontent from fans of 2008’s found-footage monster smash Cloverfield; fans of that film have been desiring a follow-up for years, and 10 Cloverfield Lane’s title seems indicative of something akin to a sequel, or at least a successor, to the 2008 hit.

And 10 Cloverfield Lane is not that film — at least not on the surface. For most of its duration, Lane is a tense, claustrophobic psychological thriller, a far-cry from the horror and bombast of the first Cloverfield. Lane centers on Michelle (Mary Elizabeth-Winstead), a young woman who finds herself in the captivity of a strange, possibly malevolent man named Howard (John Goodman). Howard claims that some cataclysmic event has devastated the outside world, and has taken Michelle and a man named Emmet (John Gallagher Jr.) into his care in the safety of his underground doomsday bunker.

The central conceit throughout most of the film hinges on how much of what Howard says is true. As the film progresses, the viewer’s perception of Howard ricochets between extremes: at one moment, viewers are bound to look upon the man with disgust and disdain; the next, they’ll take back every bad thought they ever had about him, convinced he’s just an eccentric good samaritan. John Goodman’s tremendous performance sells the character’s inconsistent persona so thoroughly that it’s made nearly impossible to accurately guess Howard’s true character at any given time.

Yet this facet of the film, as well as the overarching mystery of what really lies outside the bunker, are both tantalizing to try and guess. Much of the appeal of 10 Cloverfield Lane lies in this element of viewer participation in the proceedings, in viewers trying to guess just what the hell is actually going on. It’s an enormously fun experience, albeit one that likely loses much effectiveness after the initial viewing. The payoff that comes at the end is satisfyingly wild, though it can’t top the taut effectiveness of the film’s former portion.

So, obviously, 10 Cloverfield Lane doesn’t have much in common with Cloverfield, right? Hell, director Trachtenberg has come right out and said that Lane doesn’t even take place in the same universe as Cloverfield. And producer J.J. Abrams has likened the relationship between the original film and this “blood relative” to that between two rides at the same amusement park — a garbled, vague analogy, to say the least.

But when one accepts the fact that Lane isn’t a direct sequel, or any sort of continuation, or an attempt at a direct origin story hidden behind the veneer of a “quasi-prequel” (I’m looking at you, Prometheus), a thematic parallel can be drawn between Cloverfield and 10 Cloverfield Lane: both films revolve around the concept of being utterly clueless and helpless in the face of an incomprehensible disaster. In both films, the main protagonists, and, by extension, the viewers, are completely in the dark as to what is going on, and are struggling constantly to understand the insanity of the events taking place. Although the two films convey their terror in very different ways — one is a shaky-cam scream-fest and the other a slow-burn shocker— they’re both terrifying for basically the same reason.

Well then, one realizes, maybe this wasn’t just an elaborate marketing scheme to cram more people into 10 Cloverfield Lane theaters. Maybe J.J. Abrams really does have a master plan for his Cloverfield franchise, one that involves the production of films that are thematic brethren rather than just a bunch of cookie-cutter “the monster has returned” movies trying to emulate the success of the original, which hinged so much on audiences knowing almost nothing about it going in aside from the few details revealed by the film’s cryptic viral marketing campaign. In the internet age, where information about films spreads like wildfire and the trailers for most blockbusters reveal every major plot point of the movie, perhaps audiences crave the rare films that allow them to go in completely blind, to have totally virgin viewing experiences, to be shocked and surprised and satisfied instead of just the last one.

Or, maybe it was an elaborate marketing scheme with no master plan to back it up. In that case, so be it; the film is great and deserves to make boatloads of cash in order to encourage more like it. So long as Lane makes a bunch of money, the result could very well be the same whether or not it was planned from the beginning as having a connection to Cloverfield: an added shot of quality mysteriousness to Hollywood’s output. I, for one, would welcome such a trend with open arms, and I’m sure I’m not alone.

Comments

Post a Comment